Overview

Introduction

Over at the R Language subreddit, a college student has an interesting problem prompt. The redditor writes:

Hi, the question asks us to create a sample of standard normal distribution, n=100. Then group it into 10 groups of 10 numbers in ascending order (group 1 is the 10 smallest numbers, where group 10 is the 10 largest numbers). I then struggle on this part, “Give a vector of values (let’s call it y) which says which group each observation falls in, in the original vector x. So if the first entry in x falls in the fifth group the vector y will have at first entry value 5 and so on.”

Another helpful redditor links to a question thread over at Stack Overflow which roughly boils down to “just use cut”. That’s not so fun. Maybe we can tackle the problem differently.

Instead, let’s solve the problem using hash tables. For those not in the know, a hash table is a standard computer science data object that consists of key, value pairs. Python’s dict objects are an example. Hash tables are usually generated through the application of a hash function, which takes some standard data object and associates it with key values in a useful manner.

In R, we can do all of this with lists. The name will be our key, and the stored object will be our value. It might be a little old fashioned, but “hashing” a vector can teach us a lot about lists in R and functions in R. Many new users might not recognize how powerful these objects actually are.

Building a hash table

Let’s begin. As always, let’s grab a couple packages. As I prefer functional programming in R, we’ll be using magrittr today.

library(magrittr)If you haven’t seen this package before, please check out its wonderful introductory vignette. To cut to the chase, magrittr implements a “pipe” with the infix function %>%. The pipe takes some like this

f(g(x), y)And turns it into this:

x %>% g %>% f(y)Specifically speaking, the pipe moves the left-hand side into the first argument of the right-hand side. If it’s the only argument, you don’t even need to provide parentheses. If you don’t want the left-hand side to be the first argument, use can set the exact spot with a dot .. It’s pretty amazing, and there are many other functional manipulation tools in the package. Seriously, read the vignette (or at least read it when you’re done here).

Like the Wikipedia article explained, we need a hash function in order to use hash tables. Here’s one.

# Separate a vector into equal-value bins, cut reallocates overflow

hash <- function(x, nbins) {

seq_along(x) %>% cut(nbins, label = FALSE) %>% split(sort(x), .)

}Our hash function implements an algorithm consisting of three functions.

seq_alongtake any vector and generates an integer sequence of the same length.cuttakes a numeric vector and divides it intonbinsintervals. Setting thelabelargument toFALSElets us keep the bin number as the label. This will be the key component of our hash table.splittakes a factor or an object that can be coerced into a factor and divides the vector into groups. We will sort our input vectorxto make the grouping more meaningful.

This function should output a list of length nbins with a vector in each bucket. Using cut has the advantage of controlling overflow. If the modulo division of the length of x by the number of bins does not equal zero, cut will automatically select which buckets receive the extra values. This saves us from having to write code to check if the vector can be “equally” divided by the number of bins we want.

Searching for values

Now that we can hash numeric vectors, it would be nice to take a value y and find it in our buckets. First, let’s make an function to check if a value is within a sequence.

# Check to see if a value is within the values given by an array

is_within <- function(vec, y) {

(min(vec) <= y) && (y <= max(vec))

}

is_contained <- function(vec, y) {

y %in% vec

}Note that we have two different definitions of “within” above. For continuous variables, we would want an idea of “within” that encompasses the range of the variable. For discrete variables, we might prefer a “within” function that checks to see if that exact value is in the bin.

With these functions in hand, let’s apply them to our the table.

# Find list entry that contains a value y

lookup <- function(y, list, within_function = c("is_within", "is_contained")) {

FUN <- within_function %>% match.arg(c("is_within", "is_contained")) %>% get

vapply(list, FUN, y = y, logical(1)) %>% which(useNames = FALSE) %>% subtract(1)

}The first part of lookup allows us to use the a string in the arguments to get either of our first two functions. First, we ensure that the user has supplied one of the two acceptable function names, then we use get to retrieve it. Next vapply calls the function use each vector in contained in the entries of the list, resulting in a logical vector. which tells us which entries in the logical vector are TRUE, and we subtract 1 in order to index from zero. This should make the Computer Scientists happy (I hope you’re happy).

For convenience sake, we should immediately combine the preceding functions into a single call.

# Combine the previous functions

a_hash_lookup <- function(y, x, nbins = NULL,

within_function = "is_within",

names = TRUE) {

# Assert input

if (!is.list(x) && is.null(nbins)) {

stop("Please provide either a hash table or

both the arguments to the hash function (x, nbins)")

} else if(!is.list(x)) {

x <- hash(x, nbins)

}

# Set the names value

if (names) nms <- round(y,4)

else nms <- NULL

y %>% lookup(x, within_function) %>% setNames(nms)

}

# Create a vectorized version

v_hash_lookup <- function(y, x, nbins = NULL) {

if (!is.list(x) && is.null(nbins)) {

stop("Please provide either a hash table or

both the arguments to the hash function (x, nbins)")

} else if(!is.list(x)) {

x <- hash(x, nbins)

}

y %>% lapply(a_hash_lookup, x = x, names = FALSE) %>%

setNames(round(y, 4))

}Both functions begin with a simple assertion that ensures we get either a hash table, as a list, or everything we need to make one. The important stuff happens in the return line. The first function above allows us to search for an individual value y in a hash table formed from x.

We extend that in the second, vectorized, function. Now, we can search for all of the values in a vector, and get all of their hash locations. We keep the assertion and elements to create a hash table in order to avoid creating multiple copies of the hash table when calling a_hash_lookup with lapply.

Last but not least, to solve the redditor’s problem, we create another lookup that can find values in a vector against a hashed version of itself. We provide the added option of specifying which values in the vector through the id argument.

# Self lookup

self_lookup <- function(x, nbins, id = seq_along(x)) {

if (length(id) == 1) a_hash_lookup(x[id], x, nbins)

else v_hash_lookup(x[id], x, nbins)

}Testing the lookup

Now comes the fun part, actually testing our work. We’ll start with a vector of 100 normally distributed random variables.

# Test Vector

x <- rnorm(100)Does the hash function work?

# Test hash function

hash(x, 10) %>% sapply(length)## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

## 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10hash(x, 8) %>% sapply(length)## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

## 13 12 13 12 12 13 12 13Sure looks like it. Even better, we can see how cut handles overflow. Next up, let’s test the lookup function for single values.

# Test atomic version

self_lookup(x, nbins = 10, id = 2)## 0.0123

## 5which(x[2] == sort(x)) - 1## [1] 52The second expression above, which calls which tells us the sorted position of x[2]. It is 31st largest value, since sort is ascending by default. When we use 10 bins, it is in the 3rd bucket of our hash table (again, we’re indexing from 0. ARE YOU HAPPY!?!?).

Now we make sure that our lookup can handle more than one id value.

# Test vector version

self_lookup(x, nbins = 10, id = 1:5) %>% unlist## 0.0566 0.0123 -0.6377 0.5055 -0.4368

## 5 5 2 6 31:5 %>% sapply(function(id) which(x[id] == sort(x))) - 1## [1] 53 52 26 68 32Which it does. Unfortunately, the continuous example masks an unfortunate quick lurking in our code. What if our value matches multiple bins? By default, our function returns all of the matches. For example, take a random sample of integers between 1 and 10.

# Mutliple matches

sample(1:10, 100, replace = TRUE) %>% self_lookup(nbins = 10, id = 1:5)## $`1`

## [1] 0

##

## $`10`

## [1] 9

##

## $`5`

## [1] 4 5

##

## $`10`

## [1] 9

##

## $`2`

## [1] 0 1We can see that the value 4 appears in multiple bins. We might want to create another version of our lookup to trim the results and avoid that behavior. Of course, the type of trimming we want might vary depending on the situation, so we should let the user choose. Some good options are the first, last

# Trim the results

self_lookup_t <- function(x, nbins, id = seq_along(x),

trimFUN = c("head", "tail", "median")) {

# Assert function input

type <- trimFUN %>% match.arg(c("head", "tail", "median"))

switch (type,

head = vapply(self_lookup(x, nbins, id), head, 1, FUN.VALUE = numeric(1)),

median = vapply(self_lookup(x, nbins, id), median, FUN.VALUE = numeric(1)),

tail = vapply(self_lookup(x, nbins, id), tail, 1, FUN.VALUE = numeric(1))

)

}Although it would be nice to just pass a simple function to one call of vapply, we don’t have that option. median takes only one argument by default, while head and tail both take two. To solve this, we use switch to pull the function we want from a set of possible values.

Now do we get what we want?

# No more mutliple matches

sample(1:10, 100, replace = TRUE) %>% self_lookup_t(nbins = 10, id = 1:5)## 2 2 10 7 5

## 0 0 9 6 4Sure looks like it. The output is a vector, and we have ensured no multiple matches.

Let’s do something practical

R is a language primarily designed for statisticians, and so far, nothing has resembled statistics all that much. But there are (inefficient) practical examples of the hash table lookup functions that we built. For example, what if we wanted to bin the numerical vectors in a data frame. Well, now that we have a trimmed version of our lookup function, it’s quite easy!

# A binning example

binned <- iris[-5] %>% lapply(self_lookup_t, 10) %>% data.frame

head(iris)## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosahead(binned)## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

## 1 2 8 0 0

## 2 1 3 0 0

## 3 0 6 0 0

## 4 0 5 1 0

## 5 1 8 0 0

## 6 3 9 2 2We drop the fifth column from binning iris, since it’s a factor. A factor doesn’t necessarily have an implicit order, like numeric values, and so our original hash function doesn’t make much sense. Maybe we can build a different one later.

Nonetheless, for our purposes, we’ve binned the numeric values in iris. Then again, it would be nice to include the ranges of the values as labels to our binned results as well as save the binned values as factors. After all, bins are often thought of as categorical values. If only there were a function for that. Wait… there’s cut!

# More practical

binned_f <- iris[-5] %>% lapply(cut, 10) %>% data.frame

head(binned_f)## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

## 1 (5.02,5.38] (3.44,3.68] (0.994,1.59] (0.0976,0.34]

## 2 (4.66,5.02] (2.96,3.2] (0.994,1.59] (0.0976,0.34]

## 3 (4.66,5.02] (2.96,3.2] (0.994,1.59] (0.0976,0.34]

## 4 (4.3,4.66] (2.96,3.2] (0.994,1.59] (0.0976,0.34]

## 5 (4.66,5.02] (3.44,3.68] (0.994,1.59] (0.0976,0.34]

## 6 (5.38,5.74] (3.68,3.92] (1.59,2.18] (0.34,0.58]Which answers the redditor’s question! She should probably just use cut. But at least now we have a full understanding of why!

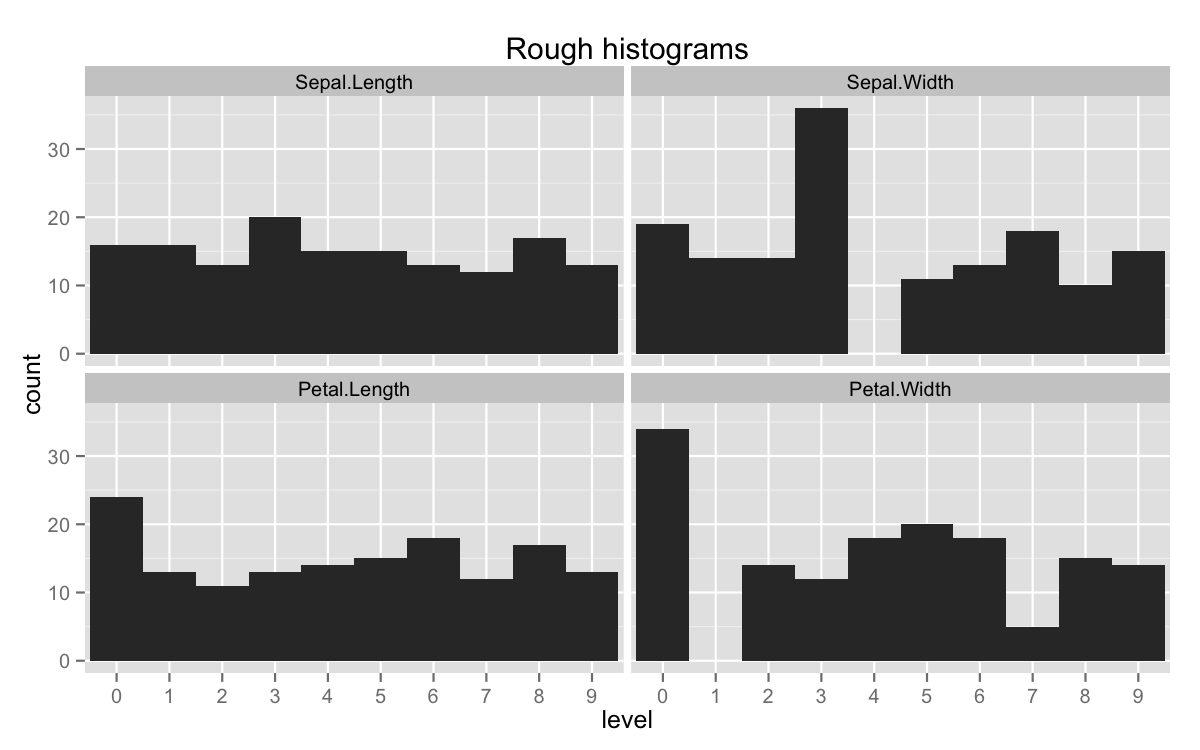

If we add tidyr::gather, we’ve surprisingly backed our way into a histogram.

library(ggplot2)

binned %>% tidyr::gather(variable, level) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = factor(level))) +

geom_bar(width = 1) +

facet_wrap(~variable , nrow = 2) +

xlab('level') +

ggtitle('Rough histograms')

This obviously isn’t the easiest way to get that plot (geom_histogram is), but it’s nice to have stumbled upon it. In general, cut should outperform the functions we’ve already written, since calls an Internal function called .bincode. All of R’s internals are written in C. The difference is pretty extreme.

system.time(iris[-5] %>% lapply(cut, 10) %>% data.frame)## user system elapsed

## 0.002 0.000 0.003system.time(iris[-5] %>% lapply(self_lookup_t, 10) %>% data.frame)## user system elapsed

## 0.207 0.003 0.211Still, we’ve essentially built a pure R framework for a function like cut. More importantly, we’ve had the chance to see some of the amazing flexibility available in R’s lists, and hopefully had a little fun along the way.