Overview

Introduction

From my long experience as Statistical blogger,1 I’ve learned that finding interesting problems is one of the biggest challenges I face. A lot of challenges are acute, like getting Google Analytics to work, but once they’re solved, they’re solved. Generating interesting content is a persistent problem. No matter how well I solve it today, it’s always coming back.

Thankfully, the ever invaluable FiveThirtyEight.com has started a new feature: a weekly statistical problem that the community can solve that they’re calling The Riddler. We already have two problems to dig our teeth into, and I’ll be working through one today.

Before we proceed, a couple of disclaimers. Obviously, the post is a set of blatant spoilers. Please, go take a stab at the problem on your own first. It’s a really great chance to learn.

Second, I want to make it clear that I have no intention of making this a place where Michael just solves a bunch of FiveThirtyEight problems. I appreciate that this is a chance to jump off and explore an entire facet of Stochastic processes. There will be more to this post than just the problem, and I have no intention on tackling these problems regularly. This problem in particular stood out because there was a lot that could be gained by solving it. Plus, it connects to a variety of classical threads in the study of stochastic processes.

So, seriously, go and try to solve the problem on your own. While you do that, I’ll just sit here and wait. Don’t worry, I’ll still be here when you come back.

A Direct Solution

Alright! Let’s start by reviewing the problem, as posted by Oliver Roeder:

You arrive at the beautiful Three Geysers National Park. You read a placard explaining that the three eponymous geysers — creatively named A, B and C — erupt at intervals of precisely two hours, four hours and six hours, respectively. However, you just got there, so you have no idea how the three eruptions are staggered. Assuming they each started erupting at some independently random point in history, what are the probabilities that A, B and C, respectively, will be the first to erupt after your arrival?

We have two big clues to take from the description of the problem. The first comes early on. Geysers A, B and C erupt a predefined fixed intervals. Since we don’t know the timing of the first eruption of any geyser, we can conclude that their eruption times are uniformly distributed within different-lengthed windows. Second, we will utlize the fact that each started erupting independently.

With this in hand, there are a variety of ways for approaching the solution. I would be remiss to not mention the approach of Jack van Riel at BoardGameGeek.com. Since each eruption occurs randomly during a fixed interval, we can divide our day into two-hour “blocks” and count the number of times each event occurs.

For example, in any two hour block, we know that A has to occur. While we don’t know the particular starting block for B, we know it follows a pattern of hit and miss. Similarly, we can’t say for sure when C starts, but it has to follow a pattern of hit, miss, miss. Here’s an example distribution of the events.

result <- data.frame(hour = seq(2, 24, by = 2),

A = rep("a", 12),

B = rep(c("", "b"), 6),

C = rep(c("","", "c"), 4))

result## hour A B C

## 1 2 a

## 2 4 a b

## 3 6 a c

## 4 8 a b

## 5 10 a

## 6 12 a b c

## 7 14 a

## 8 16 a b

## 9 18 a c

## 10 20 a b

## 11 22 a

## 12 24 a b cThere any many different ways to derive tables like the preceding. It doesn’t matter too much, since we only need to see the repeating pattern. In any 12-hour period (i.e. over six blocks):

- A occurs six times.

- B occurs three times. Every instance occurs in the same two-hour block as an A. Once, it occurs in the same block as a C.

- C occurs twice: once alone with an A and once with a B and an A.

Since the eruptions are uniform random variables, shared blocks have equal probabilities of each geyser arriving first. In the table above, if we arrive at hour four, we have a 50 percent chance of seeing geyser A erupt first, and a a 50 percent chance of seeing B first. The same follows for when there are three eruptions in the same block.

Last but not least, our arrival time is uncertain. Over a 12-hour period, we have a $\frac{1}{6}$ chance of arriving in each block. That means that our probability of seeing A first in hour eight, given the table above, is equal to the probability of arriving in hour eight times the probability that A erupts first. Formally,

Where $H$ is the hour to arrival and $T_Y$ is the time to any particular event. The overall probability of A occurring first is just the sum of every block in a 12-hour period. This is one complete cycle of the pattern.

Where $P(F = Y)$ is the probability of seeing geyser $Y$ erupt first. These sums are pretty easy to calculate by hand. All we need to do is just read down the table above. When evaluating the sum for A, if it occurs on a line alone, it gets a one. If it shares, we split the chances between the two (or three) geysers evenly. Putting this together,

To check our work, we’d want to make sure that all of the probabilities add up to one. They do.

Let’s Break Out the Math Stats

Jack’s solution is clear and direct. I hope most people can follow my description of it. On the other hand, the solution itself isn’t very generalizable. What if geyser B erupted every three hours and 20 minutes. How would we set up the table then? Let’s not, and instead, let’s tackle the problem again from a more rigorous perspective.

To start, we should think a little more about the probability statements used in our problem. For example, we could describe the probability of A being first as the union of two events. Either A erupts before B erupts before C, or A erupts before C erupts before B. Formally speaking,

The same pattern following for our other geyser’s occurring first. No matter which event we want to analyze, we need to evaluate the joint probability statements on the right-hand-side of the expression above. This approach uses a probability density function (PDF). For those that haven’t taken a Probability or Math Stats class, the probability of a given event can be found by taking the integral of its PDF. For example, assume that we have a variable $X$ with a support of $\Omega$. With an arbitrary PDF $f_X(x)$ and a subset $A \in X$, we can generally find the event’s probability by evaluating the following integral:

When we have a joint distribution consisting of $y$ variables, we need the same number of integrals to evaluate the probability statement. That means our solution needs two different components. First, we need a joint PDF for the eruptions of our geysers. And second, we need to understand the bounds for integration.

Let’s find the joint PDF first. From the original description of the problem, we have three uniformly distributed variables that differ on the length of their intervals. Formally,

Where $\theta_A \le \theta_B \le \theta_C$. This fits the description of the problem that we were given, but it makes sense to maintain this order regardless of the waiting times between eruptions.

For those not wanting to hop over to Wikipedia, the PDF for a uniformly distributed continuous variable on the interval $[a, b]$ follows:

Since each event is independent, we have find their joint PDF by multiplying their individual PDF’s.

In general, this is a simple integrand for finding the probability of each event we want. For example,

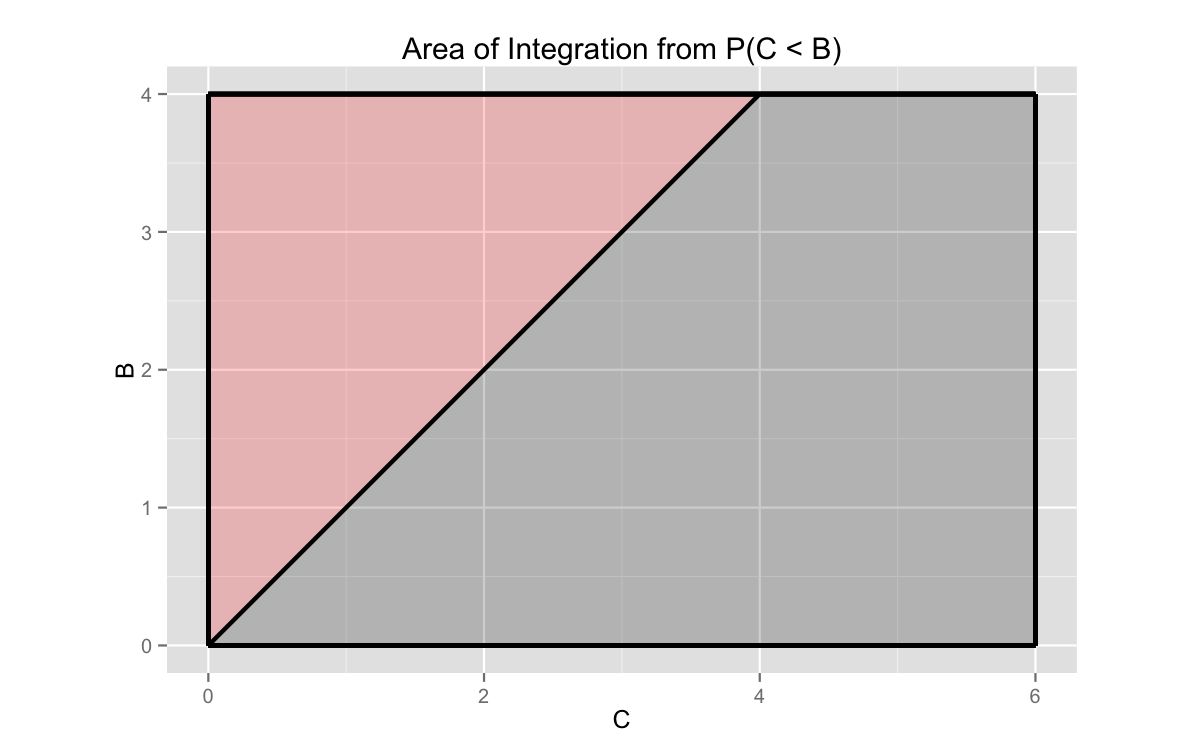

But this becomes much more complicated if the order of the inequalities is scrambled. For example, if we are interested in $P(A < C < B)$, the bounds of the middle integrand changes. We cannot integrate from 0 to $\theta_C$, because we know that $\theta_C > \theta_B$. Our variable C cannot assume a variable that is greater than the range of values for B. A picture helps clarify this.

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

data.frame(C = 0:6, B = c(0:4, 4, 4)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = C, y = B)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = 0, ymax = B), fill = 'black', alpha = .2) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = B, ymax = 4), fill = 'red', alpha = .2) +

geom_line(color = 'black', lwd = 1) +

geom_segment(aes(x = 0, y = 0, xend = 6, yend = 0), lwd = 1) +

geom_segment(aes(x = 0, y = 4, xend = 6, yend = 4), lwd = 1) +

geom_segment(aes(x = 0, y = 0, xend = 0, yend = 4), lwd = 1) +

geom_segment(aes(x = 6, y = 0, xend = 6, yend = 4), lwd = 1) +

coord_fixed() +

ggtitle('Area of Integration from P(C < B)')

We would integrate over the pink area if we wanted to evaluate $P(C < B)$ with our random variables. Even though $C \in [0, 6]$, our area of integration is bounded by the maximum value of $B$. Properly evaluating these probability statements demands that we pay attention to these bounds.

We have everything we need to find a general solution. Let’s put it all together in Python.

A General Solution

Object-oriented programming in Python

Python you say!?!?!? Yes, Python. Here at the Big Blog of R Adventures, we believe in tackling problems with the best tools available. Python has a great symbolic math package called SymPy, and I’m a big fan. The integrate function in R evaluates one-dimension bounded integrals numerically. Hypothetically, we might be able to force our problem to fit this framework, but it’s not worth the effort.

Let’s just stick with Python. It can be our little secret.

We’ll solve this problem by creating a new class, which is the Python definition of an object. I’m an intermediate Python programmer at best, so please bear with me as I try and describe it’s Object Oriented Programming (OOP) features. All apologies if I butcher a concept along the way.

According to Jeff Knupp, classes are the fundamental building block of Python. While everything in R is built from fundamental objects with every action is a function, Python builds almost everything in the language with classes. Once the classes are created, we act on them with corresponding methods, i.e. functions that take this class as an input.

Classes in Python allow us to group attributes, data and methods in a single object. This is quite different from OOP in R.2 In R, methods for objects are a part of functions that are deployed using a generic function. This generic function does the heavy lifting in deciding which methods correspond to which objects. As it turns out, R is a bit of a weird one in this regard. The most popular OOP languages just store everything you need in the class.

Classes are made with the class function, just as functions are made with the def function. Most of the other differences between creating classes and functions are mostly cosmetic, with a couple of exceptions:

- Classes have a method called

__init__, which executes the moment an object is created using the class. - Classes have a special parameter called

self, which is usually passed as the first argument in methods.selfallows you to store data in the object.

If you know how to write a function in Python, making classes is only a couple of small additional steps.

Making geysers

So, let’s make our class.

from sympy import symbols

from sympy import integrals as Int

from itertools import permutations

class geyser:

'''

This is a python-based solution to the geyser problem presented on

FiveThirtyEight.com. It uses Sympy to evaluate an integral. With that

result, we create a general function for solving with the supplied rates.

'''

def __init__(self, A, B, C):

# Define symbols

self.terms = symbols('x y z')

# Define Rates

self.bounds = [A, B, C]

# Define joint pdf

self.joint_pdf = 1 / (A * B * C)When creating our geyser object, we pass it the rate of eruptions per day. These are stored under the attributed bounds. We also create a set of SymPy symbols, which will be used to evaluate the integrals. Last, we create a generic joint PDF, based on the work we did above.

Our class has several methods. We’ll use them to evaluate all of the integrals in our problem, organize the results and produce output. The first method solves the bounds problem identified above. In the case of $P(C < B)$, the method set_bounds makes sure that we only integrate $C$ up to $\theta_B$.

def set_bounds(self, bounds):

'''

Correcting for situations where a variable with a broader

support is less than a variable with a smaller support.

'''

# Backwards checks

for i in range(2, 0, -1):

if bounds[i] < bounds[i - 1]:

bounds[i - 1] = bounds[i]

# Forwards checks

for i in range(2):

if bounds[i] > bounds[i + 1]:

bounds[i] = bounds[i + 1]

return boundsUsing two loops, one proceeding in each direction, corrects for edge cases. This isn’t the most efficient solution to the problem, but I prefer it over extra control statements. Since we only have three three sets of bounds at any one time, being inefficient isn’t that big of a deal.

Next, we create a method for evaluating one instance of our integral.

def uni_integral(self, terms, bounds):

bounds = self.set_bounds(bounds)

return Int.integrate(self.joint_pdf,

(terms[2], terms[1], bounds[2]),

(terms[1], terms[0], bounds[1]),

(terms[0], 0, bounds[0]))We call set_bounds within this function every time it is iterated. This allows the method to work a bit like an assertion, guaranteeing that the bounds are correctly identified each time that the function is evaluated. The function Int.integrate comes from SymPy. It’s the general symbolic integration solver.

It’s pretty inconvenient to manually program each different permutation of the bounds that we need to solve. We automate this in the next method.

def all_integrals(self):

integrals = []

for p in permutations([0, 1, 2]):

terms = [self.terms[i] for i in p]

bounds = [self.bounds[i] for i in p]

integrals.append(self.uni_integral(terms, bounds))

self.integrals = integralsThe function permutations comes from the library itertools. As the name suggests, it creates permutations from a list. Most importantly, the permutations always come in a predictable pattern.

from itertools import permutations

for p in permutations([0, 1, 2]):

print(p)## (0, 1, 2)

## (0, 2, 1)

## (1, 0, 2)

## (1, 2, 0)

## (2, 0, 1)

## (2, 1, 0)As you can see, each new set of permutations starts with the next digit in the series described by the list. We will use this to combine individual integrals when finding the solution to our problem. Since sets of integrals occur in a common pattern, we can just use a loop to collapse the results. Here’s a simple printing method that takes advantage of this.

def print_sol(self):

collapsed = [self.integrals[i] + self.integrals[i + 1]

for i in range(0, 5, 2)]

self.results = {i[1]: collapsed[i[0]]

for i in enumerate(['A', 'B', 'C'])}

print("P(A < B, C) = ", round(self.results['A'], 4))

print("P(B < A, C) = ", round(self.results['B'], 4))

print("P(C < A, B) = ", round(self.results['C'], 4))That’s the last method we need. If you’re interested, you can see the complete class in this Github gist. Time to show it live.

An analytical solution

Using our class is very straightforward. We create a new object using the class function, passing our daily rates. Next, we call all_integrals() to produce all of the possible probability statements. Once the integrals are evaluated, we show our result with the printing method.3

from geyser import geyser

my_geyser = geyser(2, 4, 6)

my_geyser.all_integrals()

my_geyser.print_sol()## P(A < B, C) = 0.6389

## P(B < A, C) = 0.2222

## P(C < A, B) = 0.1389In case you were wondering:

c(23/36, 8/36, 5/36) %>% round(4)## [1] 0.6389 0.2222 0.1389We’ve found the same answer both times. It’s possible that both approaches are incorrect, but it is certainly less likely. While we could have found this answer using the much simpler method described above, the work put into this solution has resulted in a whole lot of additional utility. For example, what about those weird intervals that don’t fit easily into a table. Well, we can easily solve that one too!

from geyser import geyser

my_geyser = geyser(2.25, 3.97, 5)

my_geyser.all_integrals()

my_geyser.print_sol()## P(A < B, C) = 0.5766

## P(B < A, C) = 0.2409

## P(C < A, B) = 0.1825Getting an analytical solution from any other approach is considerably more difficult.

Since this solution is based on the PDF of each random variable, there is other useful information that we can learn about each geyser. The uniform distribution is very easy to work with, and most of these identities are already published on Wikipedia. For example, arriving at a random point in the day,

- The expected waiting time to geyser A is one hour, with a standard deviation of $\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}$ hours or 34.64 minutes.

- The expected waiting time to geyser B is two hours, with a standard deviation of $\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{3}$ hours or 69.28 minutes.

- The expected waiting time to geyser B is three hours, with a standard deviation of $\sqrt{3}$ hours or 103.92 minutes.

It’s hard to get a good sense of just how long these wait times are, but evaluating one more set of probability statements should give us a better sense.

This is a pretty simple integral. Solving it, we find that $\theta = .95$. In other words, 95 percent of the time, you can be waiting between $0.05$ hours (3 minutes) and $1.95$ hours (117 minutes) to see geyser A after arriving. That’s a huge interval, and it should give you a better sense of just how much uniform variables vary.4 Similarly,

- 95 percent of the time you visit geyser B, you’ll wait 0.1 hours (6 minutes) to 3.9 hours (174 minutes)

- 95 percent of the time you visit geyser C, you’ll wait 0.15 hours (9 minutes) to 5.85 hours (351 minutes)

So, are we right or what?

Building a geyser simulator

We now have two analytical solutions that have resulted in the same answer. We can be confident, in the least, that we didn’t somehow screw up a calculation. That said, we shouldn’t become overconfident that our analysis led to the correct answer. In both cases, we made assumptions about the distributions of the variables in our problem. What if these assumptions were wrong?

Thankfully, there’s an easy way to test them. Simulation! R is great at simulation! Simulations are a great chance to apply functional programming techniques! Everyone wins!

We’re going to tackle this simulation by building up from several simple functions, which we’ll ultimately assemble in a general function wrapper. In practice, this wrapper is just a glorified pipeline, but it will be nice to be able to call our simulation as a single function. In particular, we can add a class and use it to implement summary and plotting methods.

As always, the functions we’re working through are available in adventureR, this blog’s R package. I’ve grouped all of the geyser-related functions in a single file, and added a couple new functions to utils.r. If you’re interested, please go check them out.

The first step is to create a little object with the geyser class. This will give us some extra utility by allowing for flexible input, handling assertions and interactions with S3 generics. The most important of the latter is simulate, which will form the basis of our experiment. Here’s the class generator.

geyser <- function(...) {

ls <- list(...)

# Allow for list or ... input

if (is.recursive(ls[[1]])) rates <- unlist(ls, recursive = FALSE)

else rates <- ls

# Assertions

## No nested lists

if (is.recursive(rates[[1]])) stop("Cannot handle nested lists")

## More than two geysers

if (length(rates) < 2) stop("The number of geysers should be >= 2")

## Correct names

if (is.null(names(rates))) stop("The list of eruption names must be named")

if (anyDuplicated(names(rates)) > 0) stop("The names of the geysers must be unique")

structure(rates, class = "geyser")

}Our class simplifies our life in a couple ways. First, it takes advantage of some of the most common applications of non-standard evaluation in R. We can pass the function either named values geyser(a = 1, b = 2) or a list of values when creating a new geyser. It has some defensive programming features, too. The generator throws an error if our list is nested, we have only one geyser, or if we have duplicate names or missing names.

We start the simulation with a simple function for generating random eruption times for a single geyser. It takes an eruption rate as an argument, which describes the number of hours between eruptions, and a timeframe for the simulation. By default, the latter is set to the largest rate passed to the simulation.

eruptions <- function(rate, timeframe) {

# Given a rate, create a random start time

start <- runif(1, 0, rate)

# Produce the sequence of eruptions over the timeframe (plus 1 to get all cases)

intervals <- rep(rate, timeframe / rate + 1)

Reduce(`+`, intervals, init = start, accumulate = TRUE)

}For a single geyser, we need a random start time. Then, we create a vector of fixed intervals within two intervals of the timeframe. The additional interval ensures that we don’t encounter a situation where we arrive at the park at the end of the day and “TIME ENDS” before another eruption. We’ll assume no apocalypses today.

Next, we use the previous function to generate eruption schedules for all of the geysers in our problem.

geysers <- function(rates, timeframe) {

# Create a list of eruptions for multiple geysers

map(rates, eruptions, timeframe)

}We iterate over the list of rate’s with map, which is part of a suite of iteration tools in the functional programming library purrr. You’ll see a lot of this package today, and if you’re not familiar with it, you might enjoy reading this chapter from Hadley Wickham’s book on Data Science.

map and its cousins are similar to lapply and other functionals in base, but they are much more flexibile and useful. They come in a variety of flavors, and I’ll do my best to explain each as we go.

Next, we calculate the time of the first eruption for each geyser, given a random arrival time within the timeframe.

first_eruption <- function(geysers, arrival) {

wait_times <- map(geysers, ~ .x - arrival)

map_dbl(wait_times, ~ detect(.x, is.positive))

}The list wait_times is the result of subtracting our arrival time from each geyser’s time of the eruptions during the day. The formula within map is a shorthand for creating anonymous functions. The variable .x is a pronoun in that anonymous function. It takes the place of typical R syntax of function(.x) .x.

The first eruption we see is the first non-negative wait time in each vector. To find this we:

- Apply a simple predicate function

is.positiveto see which values are greater than 0 - Filter out the

FALSEcases withdetect(frompurrr) - And iterate over all of the geysers with

map_dbl. The suffix asserts that the function outputs a numeric vector. It is equivalent tovappply(..., numeric(1)).

We create a new vector of first eruptions for each iteration of our simulation, giving us a list of vectors. We apply another iterator to find the first eruption each time.

map(first, ~ compose(names, which.min)(.x))compose is another purrr function. It composes functions. Shocking, I know. Our composition is equivalent to names(which.min(.x)). Using compose makes it much easier to read and reason about. It’s even better when we need a composition consisting of several functions.

Now that we know which geyser erupts first each simulation, we need to do some counting. This helper function counts the number of times a provided level appears in a vector.

count_v <- function(level, vector) {

sum(vector == level)

}And this function iterates the preceding both over a set of levels and a set of vectors.

count_seq <- function(vector, levels) {

n <- length(vector)

ids <- map(seq_len(n), ~ seq_len(.x))

map(ids, function(id) map_int(levels, count_v, vector[id]))

}It’s important to note the process of creating ids, which indexes our vector from 1 to n at each step of our simulation. In other words, in step 10, we’re counting the number of first eruptions for all simulations up to 10. map_int asserts that the output of our function is an integer.

Now that we have our rolling counts, the last step is creating relative frequecies.

freq <- map2(counts, seq_len(n), ~ .x / .y)map2 iterates over two lists/ vectors simultaneously. Not surprisingly, it requires these objects to be the same lenth. With map2, we get a second pronoun .y, which is the denominator in our calculation of the rates.

With all of these parts, here’s what we built.

simulate.geyser <- function(object, n, timeframe = NULL, seed = NULL) {

# Basic assertions about n

stopifnot(length(n) == 1)

# Set the timeframe

if (is.null(timeframe)) timeframe <- max(flatten_dbl(object))

# Set the seed

if (!is.null(seed)) set.seed(seed)

# Generate the simulated geyser eruption times

simulations <- rerun(n, geysers(object, timeframe))

# Find time until the first eruption of each geyser

first <- map2(simulations, runif(n, 0, timeframe), first_eruption)

# Get the name of the first geyser to erupt

first_geyser <- map(first, ~ compose(names, which.min)(.x))

# Set the names

nms <- set_names(names(object), names(object))

# Count the number of eruptions for each geyser over n simulation

counts <- count_seq(first_geyser, nms)

# Get the frequency of eruptions

freq <- map2(counts, seq_len(n), ~ .x / .y)

# Create an index

index <- seq_len(n)

# Output results

results <- list(counts = data.frame(n = index, do.call(rbind, counts)),

frequencies = data.frame(n = index, do.call(rbind, freq)),

first_eruption = data.frame(n = index, do.call(rbind, first)),

n = n,

rates = unclass(object))

structure(results, class = "simulate.geyser")

}The complete simulate.geyser function has extra arguments and a class assignment, which should make it a little more useful. In that regard, I also created default summary and autoplot methods for our geyser simulation. I won’t be walking through them here, but please have a look if you’re interested.

The results

Now that our geyser_simulation is ready to go, let’s see her in action. We create a list of rates and produce a new geyser object with our simulation function. Each rate needs a unique name; it’s used as the name of the geyser. As the problem described, we have geysers A, B and C erupting at intervals of two, four and six hours.

library(adventureR)

my_geysers <- geyser(a = 2, b = 4, c = 6) %>% simulate(5000)And here are our results.

summary(my_geysers)##

## A geyser simulation with the following parameters:

##

## Number of eruptions, per hour:

## a b c

## 2 4 6

##

## Number of simulations:

## 5000

##

## Results:

## Over time, number of first eruptions and relative frequency:

##

## n a.count b.count c.count a.freq b.freq c.freq

## 500 317 112 71 0.6340 0.2240 0.1420

## 1000 632 216 152 0.6320 0.2160 0.1520

## 1500 959 331 210 0.6393 0.2207 0.1400

## 2000 1262 458 280 0.6310 0.2290 0.1400

## 2500 1583 566 351 0.6332 0.2264 0.1404

## 3000 1904 675 421 0.6347 0.2250 0.1403

## 3500 2223 794 483 0.6351 0.2269 0.1380

## 4000 2528 913 559 0.6320 0.2283 0.1398

## 4500 2845 1026 629 0.6322 0.2280 0.1398

## 5000 3187 1128 685 0.6374 0.2256 0.1370

##

## Relative proportions in final states, standard errors and

## approximate 95% confidence intervals:

##

## Geyser Final Rate Std. Error Lower Upper

## a 0.6374 0.006799 0.6241 0.6507

## b 0.2256 0.005911 0.2140 0.2372

## c 0.1370 0.004863 0.1275 0.1465

##

## Expected wait times for first eruption (in hours),

## standard errors and approximate 95% confidence intervals:

##

## Geyser Expected Wait Std. Error Lower Upper

## a 1.014 0.008059 0.9979 1.030

## b 2.007 0.016321 1.9754 2.039

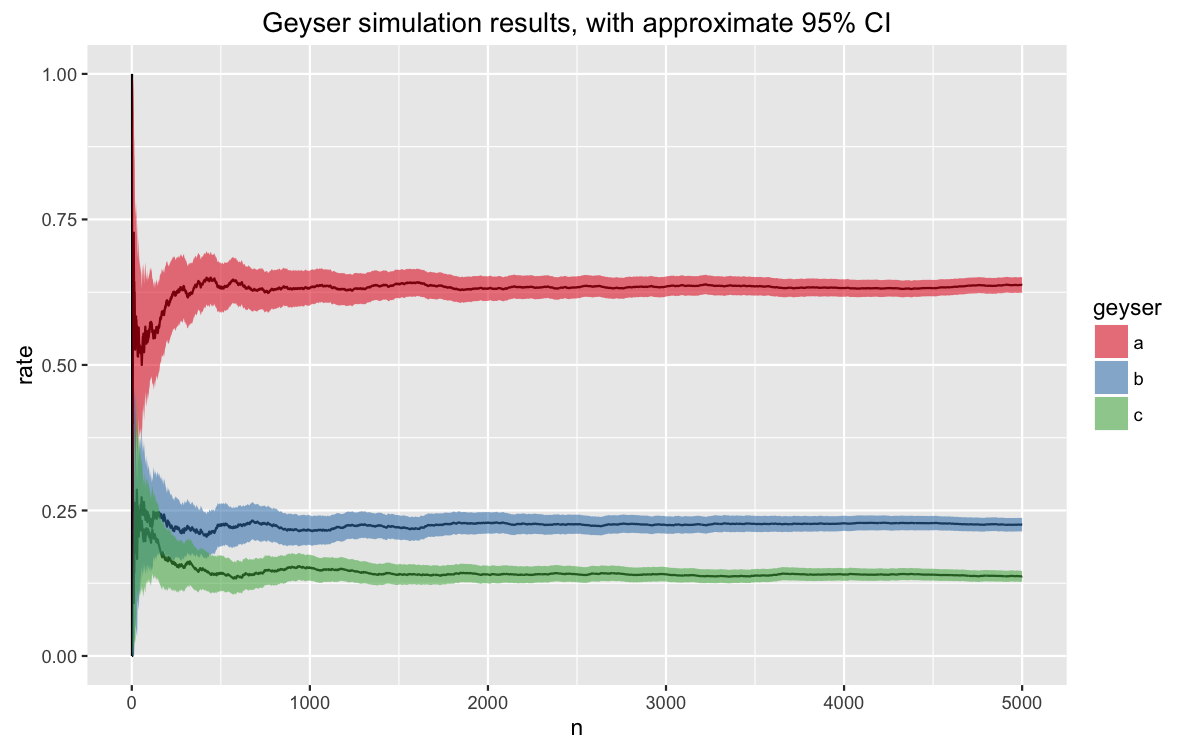

## c 3.017 0.024317 2.9694 3.065In the first table above, we see that the simulation converges relatively quickly, which is always a good sign. All of the rates we found analytically fall within the confidence intervals of our estimated rates. As do our estimated expected values.

A plot of our simulation does a better job of showing how quickly we converged to the answer. We can also see that additional simulations help narrow the error bands a bit.

autoplot(my_geysers)

Ladies and gentlemen, I think we have correct solution. In case you were wondering, FiveThirtyEight solved the problem the same way Jack van Riel did. But I have to say, I think we learned a bit more along the way. Thank you for sticking with it.

Where do we go next?

We could continue to work with the uniform distribution to learn more about our geysers. We could evaluate different probability distributions or come up with more strange eruption intervals. And I welcome you to take that on yourself. Feel free to install the blog package and experiment with the simulator too.

As for me, I’d like to start thinking about the problem a little differently. In fact, this was how I (incorrectly) first formulated it. Yes, that’s right. I originally submitted the wrong answer to FiveThirtyEight. Oops. Consider this my small way of making ammends for that mistake.

As it turns out, when modeling stochastic processes, uniform random variables are pretty rare. It’s not that common for physical systems to occur at precisely defined intervals (in either time or space). Instead, the number of times most iterative processes occur follows a Poisson distribution, and these processes are generally called Poisson point processes.

The time between these events can be modeled by an exponential distribution. This tool opens up a range of possible applications, including modeling populations, waiting times and the movement of objects through space. We’ll tackle some of this soon.

-

I’ve already made it to four posts! That must qualify me for something. ↩

-

This is only true for S3 and S4, the most common OOP systems in R. Reference classes, another OOP style in R, does keep methods within objects. This makes RC more like Python, Ruby or Java. ↩

-

One quirk of this blog’s build tools is that I can’t cache Python results. Normally, when working in R, objects created in one chunk can still be evaluated by

knitrin later chunks. Not with Python. Normally, you don’t need to repeat theseimportstatements. One is enough. ↩ -

Alternatively, we can take advantage of the fact that we know that the PDF returns an equal value at all points across the interval. An event that has a 95 percent probability would cover 95 percent of the interval. ↩