Overview

Introduction

John Marden was a Professor Emeritus when I attended UIUC. While I didn’t have the chance to attend any of his classes, he had a huge influence on my academic career. He is the author of an incredible series of “Old School” courses notes on a variety of topics in statistical analysis.

- Mathematical Statistics: Old School was my text for PhD-level math stats

- Analysis of Variance: Old School was my theory linear models text

- Multivariate Analysis: Old School was the textbook for my multivariate class

In honor of Dr. Marden, we’re doing fitting some Old School classification models to an Old School Machine learning dataset. I’ll be looking at two models today: linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and Naive Bayes (NB). I’ll touch a bit on the theory behind each model and the classification problem itself. Most importantly, I’ve developed code to implement each model, as I think both are excellent learning opportunities.

In that regard, this blog now has a package. You can find it on Github, and you can install the most recent version with devtools.

# install.packages("devtools")

devtools::install_github("michaelquinn32/adventureR")Code is a means of communication, and good code is well-documented code. The easiest way to do that was just put the package together and throw in Roxygen headers for each function. That said, the blog’s sister package is only meant to illustrate the exercises on the blog. It is permanently a work in progress, and nothing was written for perfect application in every context. Caveat emptor.

In today’s post, I’ll be working with the Hewlett-Packard Spam Data. It’s available in the UCI Repository Of Machine Learning Databases. While it’s not that old as far as standard statistical datasets are concerned (the data were published in 1999), it’s already considered a classic classification dataset. The familiarity of the data should help us focus on the real issue at hand, the classification algorithms.

The Problem

A Formal Description of Classification

Consider a multivariate dataset that consists of a $n \times p$ set of predictors $\mathbf{X}$, with $p$ columns corresponding to different variables and $n$ rows for each observation. We assume that each row is independently distributed. For classification problems, each observation belongs to one of $K$ groups described by the length-$n$ vector $y$.

Terminology is always a bit of a problem, but I’ll do my best to adhere to the terminology outlined by Hastie, Tibishirani and Friedman in The Elements of Statistical Learning. The vector $y$ is our outcome or target, and our problem is one of supervised learning. In the spam dataset, an observation can belong to either the “spam” or “not spam” group, meaning that our problem is binary.

A prediction is ultimately a function. Given a single observation of $\mathbf{X}$, let’s call is $x_j$ we want a function that produces our best estimate of the target $\hat{y}_j$. Formally, we want $\mathrm{G}()$ such that

What do we mean by “best” estimate of the target? Well, that’s a bit of a tricky question. Informally, we could define “best” as the estimator that gets us closest to the target. For whatever reason, statisticians prefer to formalize this statement through a loss function ($L$), which is a statement about our error. Here, we’ll use $0-1$ loss:

Our risk is the expected value of our loss function,

Expanding for a finite number of observations $n$, we get

If you dig through a Math Stats book for awhile, you’ll come across the property that the expectation of an indicator function is just the probability of the event. Let’s plug that in.

Minimizing our risk is equivalent to minimizing the probability statement in the left-hand side. Moreover, this minimization problem is equivalent to maximizing a slightly different probability statement. Thanks to the complement property of probabilities,

This gives us what we’re ultimately looking for. We want a function that maximizes the probability that our prediction is the same as the target, given the data that we have. Formally, that’s

In a multi-class problem, we would need to calculate the probability for each class separately and then pick accordingly. In the binary case, finding the max is much easier. Let $\mathrm{G} (x_j) = 1$ if

We can also just treat this as a ratio. This has some nice mathematical properties once we implement our different classifiers.

The fraction on the right-hand-side is known as an expression of odds. For a variety of reasons, it is often much easier to work with the log odds. This implies that $\mathrm{G} (x_j) = 1$ if

The Naive Bayes Classifier

A lot of the differences in our models come from how we evaluate the probability statements that form the log odds. For example, we can apply Bayes Rule. By that, I mean

In the numerator of the expression above, $P(y_i = 1)$ is called the prior probability. It is a statement about the distribution of the groups within our data. The other numerator component, $P(\mathbf{X} = x_i | y_i = 1)$, is called the likelihood. In Bayesian statistics, we often get to ignore the denominator, so we often say that the posterior is proportional to the prior times the likelihood.

Since we’re basing our classification rule on a ratio, we don’t even need to worry about normalizing constants. This is a big advantage of evaluating the odds instead of comparing the individual probability statements. Our problems simplifies to $\mathrm{G} (x_i) = 1$ if

For the Naive Bayes classifier, we assume that each column of $\mathbf{X}$ is normally distributed and independent. This is often too general of an assumption to make, but Naive Bayes tends to perform well regardless. This means that the $j$-th column of the $\mathbf{X}$ matrix now has the following pdf:

Assuming that the columns are independently distributed gives us an easy shortcut to calculating the likelihood in the definition of Bayes Rule above: the likelihood is now just the product of the pdf of each column. Formally,

Big products like this are often hard to work with, but applying the log takes the product and turns it into a sum. Plugging everything back into the odds ratio and simplifying, we get $\mathrm{G} (x_i) = 1$ if

where $p_k$ are the group proportions, $\mu_{kj}$ are the group means for each column and $\sigma_{kj}^2$ are the column variances. This is a pretty easy classification rule to implement.

Linear Discriminant Analysis

So that’s Naive Bayes. Remember, the form the of the classifier is based almost entirely on our assumptions about how we’ll evaluate the log odds. This isn’t the only viable set of assumptions we could apply. Often, Naive Bayes is too general. Instead, we could assume that $\mathbf{X}$ follows a multivariate (MV) normal distribution. That is,

The pdf for the MV normal distribution is similar to the univariate normal, with some additional matrix algebra.

Where $| \Sigma |$ is the determinant of the covariance matrix. Keep in mind that in the above equation we’re dealing with vectors and matrices, not scalars.

With this assumption, we can implement Linear or Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (LDA or QDA). The former has been around for almost 100 years now. Like most of Statistics, it was created by RA Fisher. You can read the original article online, along with everything else published in the very unfortunately named Annals of Eugenics. The name’s so bad that Wiley has to throw up a disclaimer. Ouch.

The methods differ over assumptions about the covariance matrix used in the problem. In LDA, we assume that different groups have the same covariance. We do not make this assumption in QDA. Grouped covariance makes the math in LDA a lot simpler, it also saves us from estimating a bunch of extra parameters. For that reason, QDA tends to overfit and you need a lot of data ( even more than the spam data ) to get improved performance. I’ll show that in this post, but I won’t actually implement QDA (the remaining proof is left as an exercise for the student…).

To estimate the covariance matrix in LDA, we use a pooled covariance:

Where $\mathbf{X}_{ki}$ is the $i$-th observation within the $k$-th group, and $\mu_k$ is the group mean.

Returning to the log odds and plugging in the MV normal pdf, we get the following classification rule. In LDA, this is usually referred as the discriminant function $d_1(x)$.

That’s still pretty ugly. Luckily, there are plenty of opportunities for simplification. Dropping out like terms and carrying the logarithm through the division, we get

Separating the terms that depend on $x$ from those that don’t, we get

Or more simply,

where

and

In multivariate statistics, a quadratic form is the matrix operation $a’ X a$ where $a$ is a length $n$ vector and $X$ is an $n \times n$ matrix. The calculation of $b$ above uses two of them. This expression will come in handy later.

If you haven’t noticed already, the expression $d_1(x) = a’ x + b$ follows the canonical definition of a hyperplane. In discriminant analysis it is often referred to as the separating plane. If none of those words mean anything to you, don’t worry, it’s just the multivariate definition of the classical linear equation $y = ax + b$. Formally speaking, the separating plane maximizes the ratio of two sums of squares, $d_R$,

Where $B$ is the between-group sum of squares

And $W$ is the within-group sum of squares, which is essentially the pooled covariance estimate that we described above.

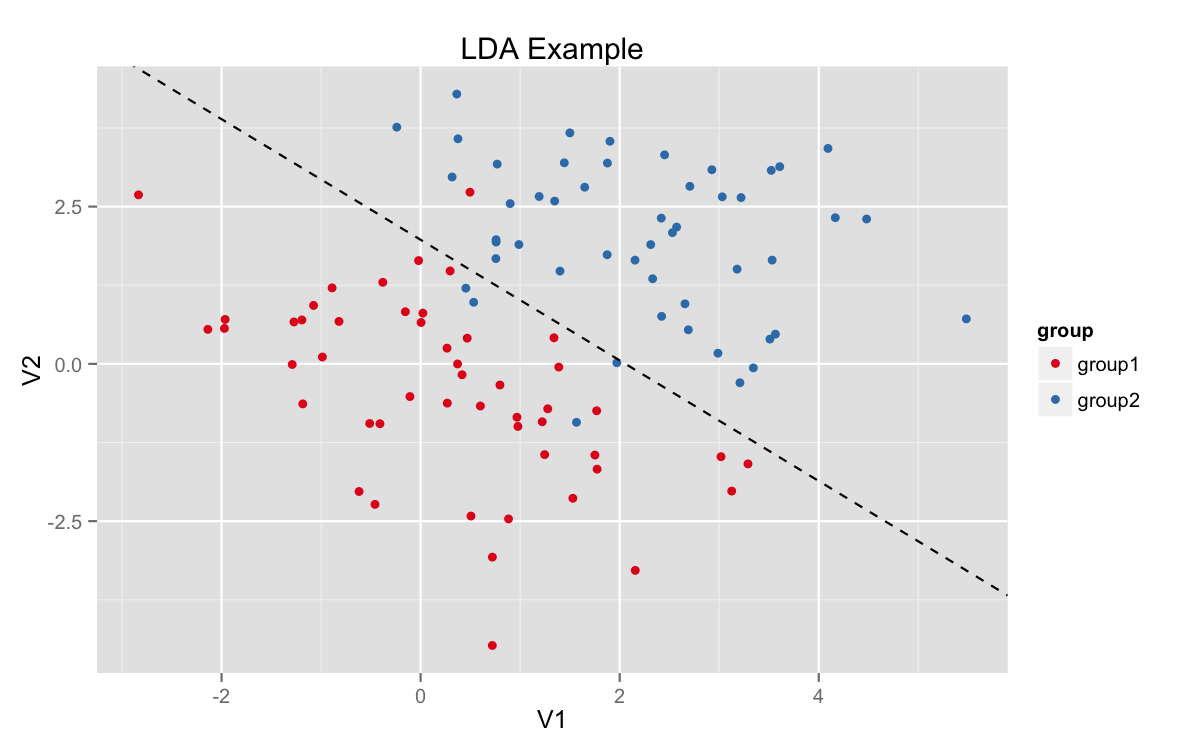

In the two dimensional binary case, it looks something like this. For now, ignore the function LDA and just focus on the image. I’ll talk about it a lot more soon.

# LDA example -------------------------------------------------------------

mus <- list(group1 = c(0,0), group2 = c(2,2))

Sigma <- matrix(c(2, -1, -1, 2), nrow = 2)

example_data <- map(mus, ~ MASS::mvrnorm(n = 50, mu = .x, Sigma = Sigma)) %>%

map(as.data.frame) %>%

bind_rows(.id = "group")

example_lda <- LDA(group ~ . , example_data)

slope <- -1 * reduce(example_lda$a, `/`)

intercept <- -1 * example_lda$b %>% as.numeric %>% `/`(example_lda$a[2])

ggplot(example_data, aes(V1, V2)) +

geom_point(aes(color = group)) +

geom_abline(slope = slope, intercept = intercept, lty = 2) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1") +

ggtitle("LDA Example")

We have two color-coded classes with a discriminating line running between them. Observations on one side of the line would be classified as one group and vice versa. Obviously, this is not a perfect classifier, but it is nonetheless optimal for a linear split.

Implementing Each Classifier

You can view the complete code for each classifier on Github. Since they’re a little on the long side, I’ll save you all from posting the complete code here. Here’s LDA, and here’s Naive Bayes. Both functions depend on the purrr package (thanks Hadley!) for some functional programming tools. You can learn about it here. If I had to pick a favorite package, it would probably be it.

The implementation of each classifier follows a similar strategy:

- Use

model.frameto convert the formula input into a standard data frame. The target is always the first column and the remainder is always the set of predictors. - Perform some assertions and clean up factors. I created a simple function

to_numberto convert a factor to numeric. It usespurrr::composeto chainas.characterandas.numeric.

to_number <- function(.factor) {

compose(as.numeric, as.character)(.factor)

}- Get the components of each equation: prior probabilities, means and variances.

- Last map the components to the data matrix and collect the results.

The mapping function does most of the work for each classification method. In LDA, the mapper calculates the equation of the discriminating plane.

preds <- apply(x, 1, function(.x) crossprod(a, .x) + b)In Naive Bayes, the mapper calculates the log odds with the column means and variances for each group.

preds <- log(p_rat) + apply(x, 1, log_odds, mus, sigmas)The function log_odds function calcates the kernel function for each class class_dist and adds the log of the variance ratio.

log_odds <- function(x, mus, sigmas) {

var_rat <- reduce(sigmas, `/`)

class_dist <- map2(mus, sigmas, ~ (x - .x)^2 / .y)

class_mat <- do.call(cbind, class_dist)

sum(.5 * log(var_rat) + class_mat %*% c(.5, -.5))

}A Test

So, which function is a better fit for our spam problem? Well, we’re statisticians. Let’s create a test.

- Randomly split

spam_datainto test and training components - Fit each model to the former and score on the latter

- Repeat many, many times (or 100 times. That’s many, many. Right?)

Since this is a classification problem, I used the F1 score as a performance metric. This score is the harmonic mean of two separate metrics:

precisionthe proportion of cases predicted to be true that are actually truerecallthe proportion of true cases classified as true.

In code, we implement this with three simple equations.

precision <- function(fit, actual) {

sum((fit == 1) & (fit == actual)) / sum(fit)

}

recall <- function(fit, actual) {

sum((fit == 1) & (fit == actual)) / sum(actual)

}

f1_score <- function(prec, rec) {

2 * (prec * rec) / (prec + rec)

}Before we get to the test, we should check out the spam dataset in detail. Let’s pull it in from the web and coerce the target into a factor. We’ll be comparing our methods against implementations within caret, and that package requires factors for classification.

# Links -------------------------------------------------------------------

spam_http <- "https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/spambase/spambase.data"

spam_names <- "https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/spambase/spambase.names"

# Get Data ----------------------------------------------------------------

col_names <- read_lines(spam_names, skip = 33) %>% gsub(":.*", "", .) %>% c("target")

col_types <- c(replicate(55, col_double()), replicate(3, col_integer()))

spam_data <- read_csv(spam_http, col_names = col_names, col_types = col_types)

# Fix target --------------------------------------------------------------

spam_data <- mutate(spam_data, target = as.factor(target))An EDA should show some potential pitfalls in the test.

# Basic EDA ---------------------------------------------------------------

summary_funs <- list(mean = partial(mean, na.rm = TRUE),

sd = partial(sd, na.rm = TRUE),

min = partial(min, na.rm = TRUE),

p25 = partial(quantile, probs = .25, names = FALSE, na.rm = TRUE),

median = partial(median, na.rm = TRUE),

p75 = partial(quantile, probs = .75, names = FALSE, na.rm = TRUE),

max = partial(max, na.rm = TRUE))

spam_data[-58] %>% map(~ invoke_map(summary_funs, x = .x)) %>%

invoke(rbind.data.frame, .) %>%

kable| mean | sd | min | p25 | median | p75 | max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word_freq_make | 0.1046 | 0.3054 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.540 |

| word_freq_address | 0.2130 | 1.2906 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 14.280 |

| word_freq_all | 0.2807 | 0.5041 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.420 | 5.100 |

| word_freq_3d | 0.0654 | 1.3952 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 42.810 |

| word_freq_our | 0.3122 | 0.6725 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.380 | 10.000 |

| word_freq_over | 0.0959 | 0.2738 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.880 |

| word_freq_remove | 0.1142 | 0.3914 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.270 |

| word_freq_internet | 0.1053 | 0.4011 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 11.110 |

| word_freq_order | 0.0901 | 0.2786 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.260 |

| word_freq_mail | 0.2394 | 0.6448 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 18.180 |

| word_freq_receive | 0.0598 | 0.2015 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.610 |

| word_freq_will | 0.5417 | 0.8617 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 0.800 | 9.670 |

| word_freq_people | 0.0939 | 0.3010 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.550 |

| word_freq_report | 0.0586 | 0.3352 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 10.000 |

| word_freq_addresses | 0.0492 | 0.2588 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.410 |

| word_freq_free | 0.2488 | 0.8258 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 20.000 |

| word_freq_business | 0.1426 | 0.4441 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.140 |

| word_freq_email | 0.1847 | 0.5311 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 9.090 |

| word_freq_you | 1.6621 | 1.7755 | 0 | 0.000 | 1.310 | 2.640 | 18.750 |

| word_freq_credit | 0.0856 | 0.5098 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 18.180 |

| word_freq_your | 0.8098 | 1.2008 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 1.270 | 11.110 |

| word_freq_font | 0.1212 | 1.0258 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 17.100 |

| word_freq_000 | 0.1016 | 0.3503 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.450 |

| word_freq_money | 0.0943 | 0.4426 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 12.500 |

| word_freq_hp | 0.5495 | 1.6713 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 20.830 |

| word_freq_hpl | 0.2654 | 0.8870 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 16.660 |

| word_freq_george | 0.7673 | 3.3673 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 33.330 |

| word_freq_650 | 0.1248 | 0.5386 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 9.090 |

| word_freq_lab | 0.0989 | 0.5933 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 14.280 |

| word_freq_labs | 0.1029 | 0.4567 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.880 |

| word_freq_telnet | 0.0648 | 0.4034 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 12.500 |

| word_freq_857 | 0.0470 | 0.3286 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.760 |

| word_freq_data | 0.0972 | 0.5559 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 18.180 |

| word_freq_415 | 0.0478 | 0.3294 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.760 |

| word_freq_85 | 0.1054 | 0.5323 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 20.000 |

| word_freq_technology | 0.0975 | 0.4026 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.690 |

| word_freq_1999 | 0.1370 | 0.4235 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 6.890 |

| word_freq_parts | 0.0132 | 0.2207 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 8.330 |

| word_freq_pm | 0.0786 | 0.4347 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 11.110 |

| word_freq_direct | 0.0648 | 0.3499 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.760 |

| word_freq_cs | 0.0437 | 0.3612 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 7.140 |

| word_freq_meeting | 0.1323 | 0.7668 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 14.280 |

| word_freq_original | 0.0461 | 0.2238 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 3.570 |

| word_freq_project | 0.0792 | 0.6220 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 20.000 |

| word_freq_re | 0.3012 | 1.0117 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 21.420 |

| word_freq_edu | 0.1798 | 0.9111 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 22.050 |

| word_freq_table | 0.0054 | 0.0763 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.170 |

| word_freq_conference | 0.0319 | 0.2857 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 10.000 |

| char_freq_; | 0.0386 | 0.2435 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.385 |

| char_freq_( | 0.1390 | 0.2704 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.188 | 9.752 |

| char_freq_[ | 0.0170 | 0.1094 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.081 |

| char_freq_! | 0.2691 | 0.8157 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.315 | 32.478 |

| char_freq_$ | 0.0758 | 0.2459 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 6.003 |

| char_freq_# | 0.0442 | 0.4293 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 19.829 |

| capital_run_length_average | 5.1915 | 31.7294 | 1 | 1.588 | 2.276 | 3.706 | 1102.500 |

| capital_run_length_longest | 52.1728 | 194.8913 | 1 | 6.000 | 15.000 | 43.000 | 9989.000 |

| capital_run_length_total | 283.2893 | 606.3479 | 1 | 35.000 | 95.000 | 266.000 | 15841.000 |

The spam dataset is pretty sparse. As it turns out, this will cause a few problems for our Naive Bayes classifier. If we randomly split the dataset for cross validation, there is a nontrivial chance that one or more of our columns with be constant and have zero variance. You can’t divide by zero, and we’ll get an NaN returned.

I added a couple functions to check for zero variance columns and remove them from a data frame. This was added to the function naive_bayes().

# Zero variance predicate

zero_variance <- function(.col, .thresh) {

var(.col) < .thresh

}

# Apply to data frame and remove constant columns

nzv <- function(.data, .target = "target", .thresh = 1e-4) {

y <- .data[,.target, drop = FALSE]

.data[.target] <- NULL

id <- map_lgl(.data, Negate(zero_variance), .thresh)

cbind(.data[id], y)

}Our target is close to balanced. This is very helpful in classification, and we shouldn’t have to worry about a skewed target resulting from random sampling.

spam_data %>% count(target) ## Source: local data frame [2 x 2]

##

## target n

## (fctr) (int)

## 1 0 2788

## 2 1 1813As a check for our implementation for each method, I’ll pull out the same classification methods in the caret packaged. For all intents and purposes, this is the gold standard for predictive modeling in R. It has a wonderul site as well, which is a thorough tutorial on predictive modeling as much as it is package documentation. If we compete well with caret, we’ve done a good job. caret has LDA, QDA and Naive Bayes. We’ll use all three, along with the option of removing zero variance columns from our training data.

# Implementing the Experiment ---------------------------------------------

# Store models to be tested

TC <- trainControl(method = 'none')

NB_pars <- data.frame(fL = 0, usekernel = FALSE)

proc <- c("nzv")

models <- list(my_lda = partial(LDA, target ~ .),

caret_lda = partial(train, target ~ ., method = 'lda',

trControl = TC),

caret_qda = partial(train, target ~ ., method = 'qda',

trControl = TC, preProcess = proc),

my_nb = partial(naive_bayes, target ~ .),

caret_nb = partial(train, target ~ ., method = 'nb',

trControl = TC, tuneGrid = NB_pars,

preProcess = proc))Since we’ll be calling all of these models against the same datasets, it’s easiest to just store these as a list and invoke them. We’ll add another function called score_model() with methods for our methods and caret’s default train class. This will standardize all of our outputs and make them easier to compare.

We need a simple helper function to split the dataset.

split_data <- function(.data, .test_rate = 0.1) {

n <- nrow(.data)

svec <- sample(c("train", "test"), n, replace = TRUE, prob = c(1 - .test_rate, .test_rate))

split(.data, svec)

}And the function rerun in purrr will generate all 100 splits for us.

# Create list of random training and test dataframes

dfs <- rerun(100, split_data(spam_data))The actual test is a relatively simple pipeline. We take our list of data frames. We call each of the models with the combination of map and invoke_map. The results in a list of lists, where each item in the top level of the list contains a list of five fit models. With that, we map again. We takes the test data out of dfs and use the models in the list of lists to get our scores.

The standardized outputs of score_model, which has methods for all of the classes of models involved, makes sure that everything is eventually consistent. It’s the grease that makes the whole machine run.

results <- dfs %>%

map( ~ invoke_map(models, data = .x$train)) %>%

map2(dfs, ~ map(.x, score_model, newdata = .y$test,

actual = .y$test$target))So, what did we get? Right now, we have a pretty messy nested list. To clean this up, we need to make some data frames and bind them together. After that, we can put together a little plot. Since we’re comparing results across distinct categories (the models), a boxplot is best.

# Lets make a nice plot

results %>% at_depth(2, data.frame) %>%

at_depth(1, bind_rows, .id = "model") %>%

bind_rows(.id = "iteration") %>%

ggplot(aes(model, f1)) +

geom_boxplot() +

ggtitle("Comparison of F1 in classification models")

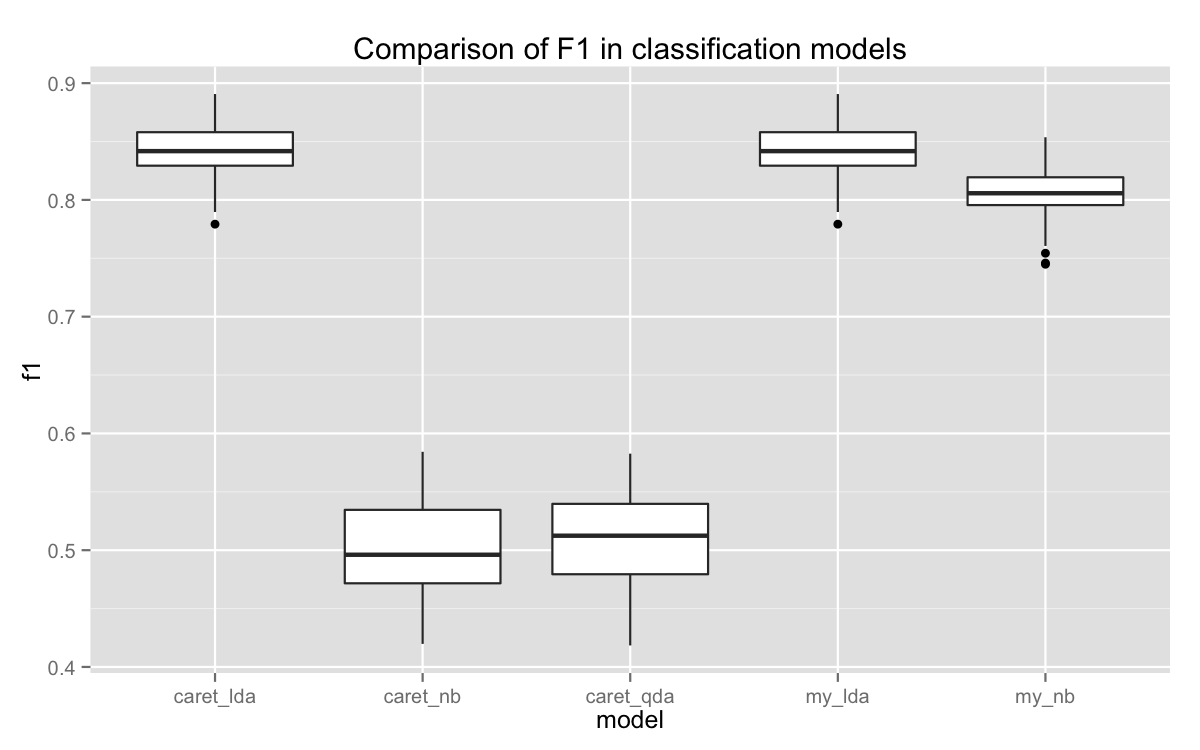

Our version of LDA performed exactly the same as caret’s. YAY! Either one is the best, but I’m pretty sure you know which one I love more.

Our version of Naive Bayes lagged a little, but it’s way ahead of caret’s QDA and Naive Bayes. Why’s that? It took awhile to diagnose, but it turns out that caret’s default correction for zero variance is pretty aggressive. So much so that it adversely affects the model’s performance. We have much tighter standards for zero variance columns, and end up rejecting a much smaller number of them.

Moreover, the version of Naive Bayes used by caret comes from the package klaR, which does not use log odds in its classification rule. There’s probably a good reason for this, but the result is something that doesn’t do that well with very sparse data frames. We get a long stream of warnings about probabilities close to 0 or 1 is the odds. It ultimately has to round, which introduces a host of problems.

We could expand on this test by throwing in some other methods, but that’s probably enough for today. Please, take the time to check out the implementation of each method in the blog’s package. It’s surprisingly simple and straightforward. And please don’t hesitate to let me know your thoughts.